Advanced analytics are taking over basketball in a big way. Stats like effective field goal percentage are slowing making their way onto broadcasts, Synergy allows the average fan to experience video breakdown the same way the pros do and NBA.com just debuted a free, publicly-available, massively powerful statistics site. The most amazing thing to me about the analytics revolution isn’t the data we do have though, but the data we don’t. There are still important, fundamental basketball questions that we don’t have answers to.

I present the following statement with zero hyperbole: we don’t know that timeouts are actually useful for most of the reasons that coaches take them.

Timeouts allow players to catch their breath and get a quick rest, and allow coaches to substitute players into the game, but that is about all we know. More often than not, coaches call timeouts to design a supposedly high-percentage offensive play or to stem the flow of the opposing team’s offensive onslaught. Coaches are just operating on guesswork, however, because we don’t actually know that timeouts effectively do these things!

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Timeouts probably depress scoring

The most compelling study on post-timeout performance was done by Beckley Mason of ESPN.com and people at NBA.com/stats. It focused on timeouts in “clutch” situations, comparing post-timeout scoring to non-timeout scoring. The research found that in each clutch situation they tested, taking a timeout actually made it more difficult for the offense to score. Shane Battier explains why:

“Defenses aren’t as prepared after a late bucket to tie or take the lead because emotionally teams aren’t as prepared to get that stop. If you call timeout you allow a team to set their defense, focus in. Everyone knows exactly what everyone runs anyway.”

Roland Beech of 82games.com came up with a different study design, focusing on the full game post-timeout performance of individual teams. He found that offensive efficiency post-timeout markedly varied among teams, suggesting that a combination of coaching and roster makeup helps some teams to better utilize timeouts. His most surprising finding was that there wasn’t too strong of a correlation between offensive efficiency post-timeout and winning percentage: some very good teams didn’t utilize timeouts well, and some very bad teams did.

Our somewhat hesitant conclusion is that, in aggregate, timeouts depress scoring in clutch situations, and some teams utilize timeouts better than others. This isn’t a lot to know, and if anything, suggests that teams should be taking many fewer time outs than they are scoring. But do timeouts work to stop runs?

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Timeouts might have a small effect on runs

For his senior thesis in economics, Sam Permutt examined the momentum-killing timeout. He restricted his study to all timeouts taken after a 6–0 run in the first half, and calculated offensive performance of the team taking the timeout during the following ten points of basketball. He found a very small benefit for the team calling the timeout, but noted such important caveats as to render the results inconclusive.

The biggest caveat is that his results weren’t statistically significant; he cannot conclusively say that the observed results reflect an actual pattern and didn’t come about by random chance. He added that in the NBA teams are fairly evenly matched (average margin of victory is 4.53 points) so in some ways the 6–0 streak can be seen as an abnormal event, and therefore post-timeout success is simply a regression to the mean.

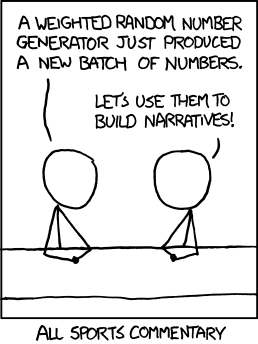

Sam’s most interesting point compares momentum to the “hot hand” theory of streak shooting, and posits that both might be the result of a misinterpretation of a random sequence of events: “The data provides more support for the idea that the belief in momentum in sports may be a perceptional bias as opposed to an accurate depiction of the inner workings of a sport.” In other words, as usual, xkcd may have been right all along.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

There are a few other studies that incorporate the momentum-killing timeout (most notably by Saavedra, Serguei, Satyam Mukherjee and James P. Bagrow) but they are either full of methodological flaws, are actually attempting to answer a different question, or both.

How little we know

…and that’s it. The definitive publicly-available work on offensive performance out of timeouts is a 1,000 word blog post, and on momentum-killing timeouts it is an undergraduate senior thesis. This statement is not made to denigrate Beckley Mason or Sam Permutt’s work, as they both have smartly-designed studies and appropriately (read: cautiously) state their non-conclusive findings and all possible flaws. But with so many professional statisticians that are interested in basketball, the Association for Professional Basketball Research, the North American Association of Sports Economists, a plethora of interested amateurs and more data than ever at our fingertips, can’t we do more?

Tools like Synergy, NBA.com/stats, Basketball Reference and Hoopdata allow us to examine ever more detailed questions, but perhaps we should take a step back. Perhaps before we dive into the data to understand how individual players perform in ever more specific situations, or how well a lineup that has only played 14 minutes together works, we could better explain basketball by gaining a firmer understanding of one of its most basic concepts: the timeout.

Thanks to Evan Zamir for his help with finding some of these studies.