Editor’s Note:This piece was originally titled “Lamenting Begrudging Greatness”. The necessary “/” was added.

***

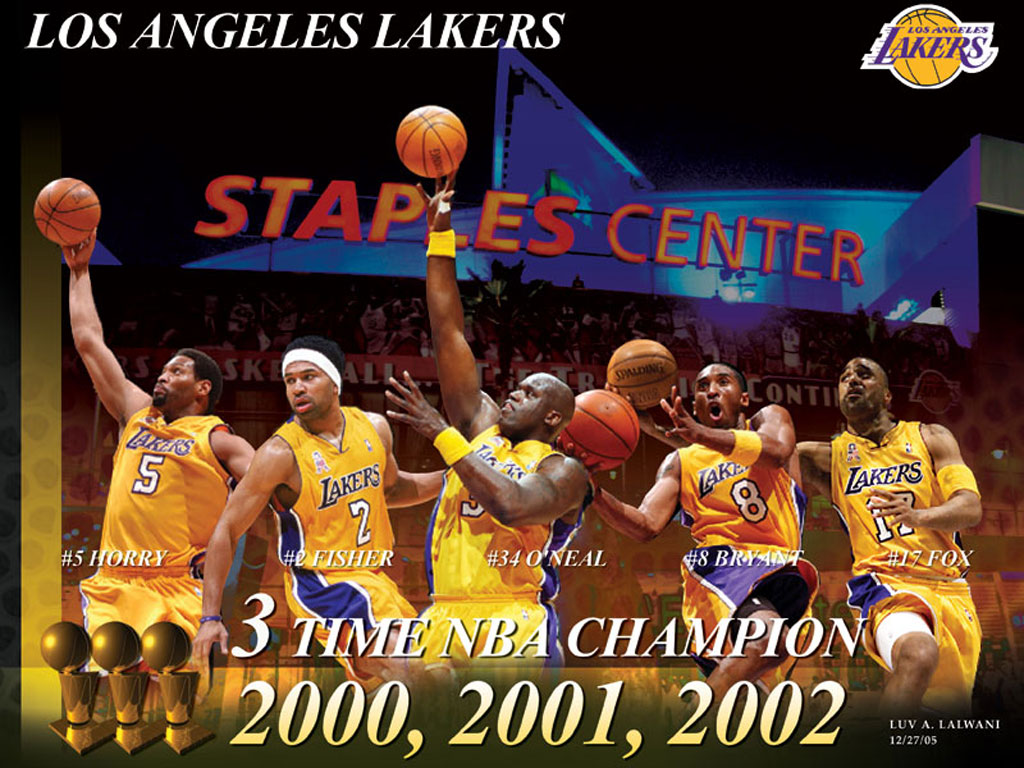

The most interesting thing in a boring night (month, really) of NBA basketball was the jersey retirement ceremony for Shaquille O’Neal at Staples Center. Shaq, of course, manned the pivot for Los Angeles for eight seasons winning several accolades, including an MVP and three NBA championships. The 15 minute (or so) ceremony featured all of the individuals you thought might speak at an event for Shaq: Kobe, Phil, Jeanie Buss and Jerry West all offered their congratulations to the massive center, who watched with smug contentment (no tears for the Big Aristotle) as his (misprinted) jersey was raised to the rafters, joining other greats like Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Wilt Chamberlain and the aforementioned West. The crowd was into it as well; they happily responded to Shaq’s egotistic “Can you dig it?” howls into the Staples Center rafters, and lustily chanted “We Want Phil!” after Shaq Diesel offered tribute to his former coach and owner of 11 championship rings. It was an enjoyable romp; certainly the most compelling event in the NBA from that particular evening.

Now, when it was all over, and the players retook the court, something was different. There was a palpable malaise that had settled over Staples Center, a tangible lowering of some sort of dial controlling the relative levels of energy and excitement in the room. As two fallen empires bludgeoned each other in a meaningless war — the Utah Jazz are looking good to make the postseason this year — it was difficult to get invested in the proceedings. There was a going-through-the-motions involved, for both teams playing in the game. The crowd who had been worked into a frenzy during the anachronistic jersey retirement ceremony quieted themselves into a teeming buzz, content to cheer when something good happened, but largely unpreturbed even when the Mavs vaguely threatened the win. There wasn’t much to feel anymore, just some anxiousness about how late the game was going on a work night. Even more troubling was that I was feeling it as well; a certain sadness that the Lakers were the Lakers that they are today.

As I have written many times before: I did not grow up a Lakers supporter. Far from one, in fact. They were the primary antagonist of my early fanhood; a smug, usurping force who couldn’t be checked until internal drama compromised their project in eternal excellence. My hatred of them was strong enough to turn me into either a Spurs, Kings or Blazers fan for the vast majority of my adolescence and I mourned like a true resident of each of those cities whenever the Lakers bested them. Losses to the Lakers continue to inspire feelings of inadequacy and inferiority within me, despite the fact I am far closer to 30 than I am to 18. Indeed, much of my NBA fanhood revolved around my specific distaste for Lakers basketball; a machine fueled by hatred and disgust. While it didn’t provide the most positive backing for a protracted interest in a specific institution, it did provide a passionate one; something I could easily get behind, and also find additional support to bolster my stance. I could get behind “Beat[ing] LA”. Lots of folks from all over the country could join that popular front; a least common denominator applicable across many different sports, for many different LA-based teams.

But what we’re watching this season? These aren’t the Lakers. This isn’t the franchise I grew to know and hate, resplendent in gold and purple, and reeking strongly of hubris and consistency. This Lakers team does not play like the Lakers, with a swagger and confidence that comes from many years of being among the absolute best in one of the most important markets in the world. They do not play hard for their coach, who cannot claim any sort of greatness from the franchise’s past achievements and who has no major achievements of his own to put on his mostly empty resume. The greats are hardly great anymore: Pau Gasol seems tentative and confused, Steve Nash is a part-time NBA player at this stage in his career, and Dwight Howard, for all of the work he’s done to get himself back to an acceptable pre-injury level, is looking more like the best member of the “good but not great Laker centers” club. The role players don’t step up to big moments in the same way Brian Shaw, Derek Fisher and Robert Horry used to, with Antawn Jamison, Jodie Meeks and Earl Clark providing bursts of excellence tempered by long periods of nothing. This is what we’re left with: a team that’s not building towards a point of true Laker-ness, but one that has failed to match the efforts of their predecessors outright.

What I’m left with is a strange sadness; something that I never truly expected to feel in connection to this team, or this franchise. While it’s an oft-repeated refrain that one “won’t miss something until it’s gone”, this is usually in conjunction to the positive things we take for granted. After watching the Lakers greats of the late 20th century and early 21st century assemble and bask in what they created — Shaq, Kobe, Phil, Jerry, the lot of them — I realize this is applicable for the things that we viewed negatively as well. For me, the Lakers created a strange but necessary balance; a hateable franchise that had the players, coaches, and general mettle to rise to the challenge and manufacture great moments. When I saw the replay of Kobe lobbing the ball to Shaq in Game 7 of the WCF against the Blazers— a game that caused the 14 year old version of myself great pain and anguish — I didn’t feel the same hurt. I didn’t feel resentment. Instead, I felt nostalgia. I felt lucky that I could remember these moments, when the Lakers were a legit threat to go undefeated in the playoffs, when it seemed like the Lakers could win a championship straight from my freshman year of high school to my senior year of college (and had Shaq not been traded, that might’ve happened).

It is for this reason — and this reason only — that I am somewhat disappointed that the grand Lakers experiment didn’t work out like most had planned. The Lakers don’t deserve greatness, no one does. But is the league better when the Lakers are great? Perhaps. Is the fabric of the league more lusty when the Lakers can legitimately portray unbridled overconfidence, and back it up with their play? Undoubtedly so. As Shaq’s Oscar-like acceptance speech (featuring no players) showed, the Lakers provide more than dominant centers and enigmatic swingmen. They provide a glitzy Hollywood package unmatched in any sport, where movie stars are part of the scenery, and deep playoff runs are treated like movie premiers. It’s not for everyone, but it is something that is part and parcel to the NBA. And while the tapestry is not totally in tatters — the Lakers might still make the playoffs, after all — it does not shine as brightly as it used to in its recent glory days.

I will be overjoyed if the Warriors make the playoffs and the Lakers don’t. But that won’t make it feel right. That, my friends, is a strange feeling.